Unweaving a tangled web: Decentralising the ownership and infrastructure of the web

Who owns the internet? There isn’t an obvious answer to the question. The internet is a labyrinthine system of hardware, protocols, and software owned and operated by a bunch of different groups. Everyone understands what the internet does, we all use it every day. Face-to-face conversations flow seamlessly with mentions of dot coms, at gmails, and hashtag trendings that lived exclusively in the text-based world just a couple of decades ago. The web, which relies on the internet to function, is the raw material that weaves the fabric of modern life.

But despite what its early adopters hoped, the web isn't a neutral force. If we want it to work for us—and not against us—we have to take control of the operation and maintenance of the internet.

These days, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft — also known as the Big Five — are pretty much running the show. How did they get so much power? Why is it a problem? Let’s take a trip through memory lane to see how we got here and what it means for the internet's future.

Caught in a sticky web (2.0)

In the autumn of 2004, the first ever Web 2.0 Conference was held in San Francisco. The brightest and best minds in the emerging internet industry were invited to discuss and plan for the future of the web. People like Jeff Bezos and Mark Cuban spoke, alongside a long list of venture capitalists, CEOs, CTOs, and all other tech power brokers.

Looking back, the sessions from the conference are an eerie mixture of warnings about the direction of the internet and sad reminders of a more hopeful time. Craigslist founder Craig Newmark gave a talk titled ‘Getting to a Billion Pages a Month without Being Evil,’ while internet legend Brewster Kahle posed a question that’s still being asked today with his session ‘Are We Inventing the Right Thing?’

These session titles have the same energy as the infamous ‘Don’t be evil’ phrase which was Google's motto in their code of conduct. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see all the amazing (and not-so-amazing) things web 2.0 has done for the internet.

It just sort of occurred to me that “Don’t be evil” is kind of funny. It’s also a bit of a jab at a lot of the other companies, especially our competitors, who at the time, in our opinion, were kind of exploiting the users to some extent.

Unfortunately, despite the platitudes espousing integrity and techno-optimism from the early days, many of the internet's powerhouses—including Google—have strayed from their noble intentions. In 2018, Google controversially removed the 'Don't be evil' motto from their code of conduct.

Nonetheless, web 2.0 completely changed what the web platform meant. The power you had, whether you were a user or an operator, was completely unlike anything the web had seen before. Web services became so convenient and usable they started making non-web solutions completely redundant. Retail transformed. Banking, too. Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram changed what it meant to have a social life. Google literally became synonymous with searching for information.

Thanks to the web 2.0 frontier, the Big Five were able to gain enormous control and influence over the global web, and over the last 15 years they’ve each kept growing and gathering power to the point where this handful of companies are able to make decisions which shape the future of the net as we know it.

What’s wrong with the state of the web

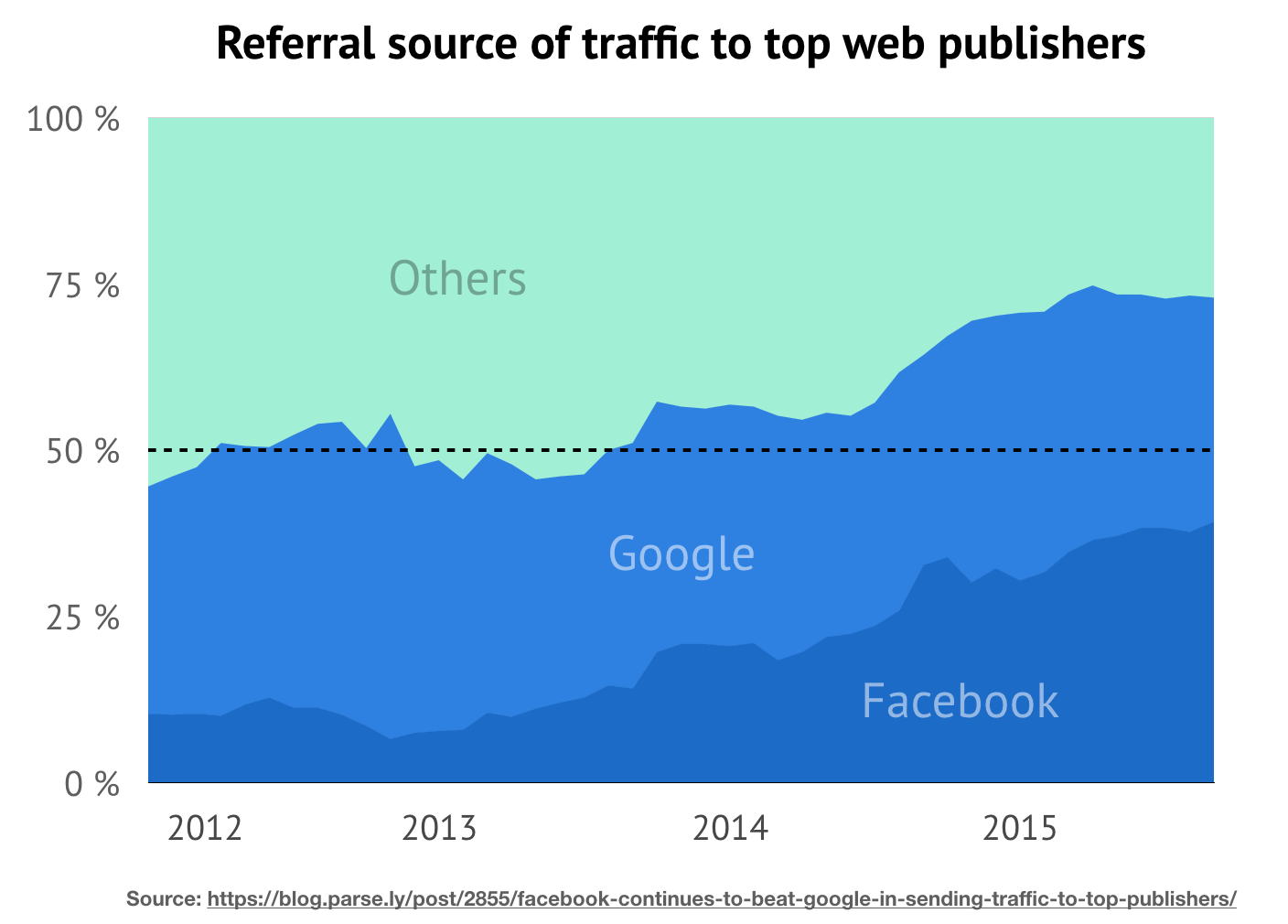

With so few companies controlling so much of the web, a lot of governance and decision making falls on the shoulders of a few key decision makers. The centralisation problem is becoming more and more severe as larger companies acquire emerging competitors and continue cornering the market. Facebook and Google are enjoying increased web-traffic dominance, and content creators are relying on platforms owned by large tech companies to reach their own audiences. André Staltz’s epic breakdown of the beginning of the end for the web paints a picture of an internet that’s becoming more popular, but less diverse — and the issue has worsened since his article in 2017.

When Facebook banned Australian news sites in early 2021, journalists, commentators, publications, and everything in between were sent into a panic as one of their main traffic sources disappeared instantly. Especially for smaller publications, traffic slowed to a crawl. Facebook eventually reversed the decision, but the incident showed just how good of a job Facebook has done making sure content creators need them. Companies like Facebook feed a manipulative relationship where even creators who are desperately unhappy with the deal being offered to them don’t have a real chance to leave the platform. Hell, even we have a Facebook page.

Most publishers feel obliged to be on Facebook . They don’t like the asymmetry of the relationship , they dislike the requirement of going through an intermediary without access to even negligible data. We have 5 years of non-platform funded research that says this.

This rampant centralisation creates a fraught situation for the future of the web. Centralised systems are vulnerable to authoritarianism, censorship, exploitation, dogmatism, and manipulation. The web can absolutely be corrupted — believing (and acting like) it’s an apolitical, amoral tool is dangerous for its future.

Censorship and misinformation are both already huge issues on these centralised platforms. Of course, platforms like Facebook aren’t non-participating — they algorithmically preference certain content, so they’re at least somewhat responsible for what content prospers and what dies. In fact, just a few years ago misinformation and fake news flourished on Facebook’s trending page when they replaced their editorial staff with an almighty algorithm.

Meanwhile, protesters in India claim Prime Minister Narendra Modi is abusing the premise of misinformation to censor legitimate criticisms of the government’s public health crisis as part of a growing trend of social media censorship in the country. The more centralised the web becomes, the more vulnerable it is to this kind of behaviour, and all we can do is hope tech companies won’t comply with blatant censorship requests.

The way the web operates nowadays is causing a huge number of issues, but these problems haven’t come out of nowhere — and people are already thinking about what the solutions should be. Projects like Oxen are building towards a new web — web 3.0. The future of the web will be powered by us — the people using it. Not executives in boardrooms trying to bolster their quarterly financial reports.

A new wide world web (again)

The new web we’re creating won’t be owned by a small handful of companies. Just like web 2.0, this doesn’t actually mean tearing everything down and starting again, it’s about creating a more compelling, more powerful, more consumer-friendly product than the one that exists at the moment.

Web 3.0 will be open, transparent, trustless, and permissionless. How? Through blockchain. Through free and open source software. By decentralising the governance (and therefore decision making) of the very infrastructure that runs the web. This will go a long way to solving a whole bunch of the issues the web is facing at the moment. The idea of web 3.0 has been around for a long time now, but tapping into the power of decentralised blockchains has taken a lot of development time. After years of hardening and improvement, we’re on the precipice of a new, better web.

The next stage of the web is the decentralized creator economy.

The very nature of a decentralised web means that anyone can participate — whether that participation is through running the server infrastructure powering the web itself, like service nodes, or by using the services, like Session. Influential thinkers like Naval Ravikant are already on board, and they’re predicting a shift towards a new, decentralised ecosystem that rewards creators.

Decentralisation puts the power of the web back in your hands — the users. The enthusiasts. The workers. The bloggers, influencers, and pundits that actually create the content that makes the web so valuable.

So far, web 3.0 has been hamstrung by the often clunky experience of dealing with crypto itself. As much as it has gotten a whole lot easier over the years — and it’ll definitely keep getting even easier — most non-traders haven’t had the skills or inclination to get involved in the space. Now, a new wave of technology that harnesses the power of web 3.0 without needing direct crypto interaction is hitting the shelves. Apps built on Oxen, like Session and Lokinet, are hardened by the blockchain infrastructure that supports them, but they don’t require users to have any crypto know-how to unlock their full potential. Naturally, as more people enter the web 3.0 space, more people will make the extra leap into cryptocurrencies as well. They might even decide they want to be a part of the network, and start running a service node.

Projects like Oxen imagine this as the future of the web — the way it was always meant to be. A web that is equal, equitable, and encourages participation on all levels. The transition has already begun, and everyone's invited.

You've got mail!

Sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with everything Oxen.